The integrity of non-western techniques of dress and decoration was demonstrated in countless instances of colonization. In conjunctions with conventional techniques of persuasion and acculturation, dress codes were often treated as integral to the process of subjugation. Along with indigenous languages, local dress codes were suppressed as if the acquisition of a new visible identity worn on the body ensured the acquisition of a new ‘modern’ cultural identity. Clothes became a weapon in the struggle between the colonisers and colonised.

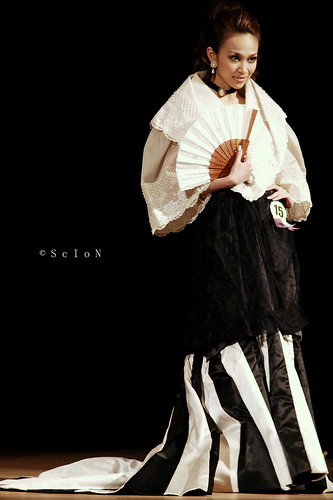

When I read this quote in Craik’s article, I was immediately reminded of the Maria Clara dress, a formal dress worn by women of the Philippines. This dress has evolved over the past 120 years, with various cuts and colors, but its origins trace back to Spanish colonialism in the Philippines during the late 1800s. According to WikiPilipinas, the dress derives from the Baro’t Saya, a blouse and skirt ensemble similar to the Barong Tagalog, the traditional male formal wear of the Philippines. Filipina women wore the outfit during the colonial occupation as a requirement by the Spanish to cover their upper torso. As the Philippines moved towards a more democratic country, however, this outfit moved from a symbol of colonialism, to a symbol of Philippine nationalism, now being worn in inaugural balls, award ceremonies, and many other important events. The name of the dress itself is named after the heroine of José Rizal’s novel, Noli Me Tangere, which symbolizes the ideal Filipina woman and national fervor.

No comments:

Post a Comment